About Us

About Us

This article was in Ceramics Monthly -May 2020

In 1980, when Donna and I first saw the abandoned two-room schoolhouse in the mountains of southern West Virginia, the front door was open. “God Loves You” and “Zorro Was Here” were both written on the blackboard. We knew immediately that this would be our home and studio. Located on a one-lane country road and set in acres of woodland that now provide fuel for our wood kiln and home, the school was a shell of a building that had no plumbing or electricity. With the help of family, friends, and neighbors, we made the space functional and started creating and selling pots in a few short months. We have added a kiln room and gallery on the studio side of the building and bedrooms on the house side. We also added sheds for the wood kiln and salt kiln and several sheds for equipment,bricks,clay,and the menagerie of essential stuff accumulated over 46 years. All the tools (even the potter’s wheels), 5-gallon buckets, glazes, and clays are on wheels for ease of movement, allowing the 20×25-foot studio to be used for all of the pottery processes. The studio has a different configuration every day to make for a smooth work flow, based on what is being done.

The two school rooms—converted into one living space and one studio—are about 500 square feet each, with large windows along one wall providing lots of natural light. We have kept the studio one big room and make use of an ever-changing layout of tables and equipment, depending on the pots we are working on. Two large, rolling ware racks stand ready for greenware or bisqueware. Shelves on the side walls provide storage for tools and glaze materials.

We have six wheels for different pots including a Leach wheel (christened by David Leach), an unstoppable, heavy-duty wheel for throwing the big pots that was made for me by a local

welding shop (you could throw a silo on it without slowing down), a waist-height electric wheel for most of the production ware, an onggi wheel (for when Kang Hyo Lee visits), and a couple of small electric wheels, all with Soldner pedals. The wheels are all stored on casters to allow easy set up.

We mix most of our clay, which is then stored in decommissioned freezers. The pugged logs of clay are gently stacked in the freezers (the shelves were removed). The freezers have seals around the doors so it is not necessary to bag the clay. The reduction kiln room is attached to the back of the building and our gallery is situated beyond the kiln room. The electric kiln used for crystalline glaze firings is located next to the reduction kiln. The wood kiln is outside, housed in a large, open, timber-frame shed with a clay-tile roof (the clay tiles were made in Alfred, New York, in 1907), while the salt kiln is in a round stone building.

Paying Dues (and Bills)

I was introduced to clay as a child by my grandfather who was a potter. For my formal training, I was fortunate to be in the ceramic apprenticeship program at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky, where I was enrolled from 1974–79. This is a pottery training program

developed by Walter Hyleck that produces a line of functional pots marketed through the college’s Student Craft Industries. Walter connected me with Wilhelm and Ely Kuch in the former West Germany, and between my junior and senior years at Berea College, I trained as an apprentice for a year at their production pottery near Nuremberg. Coincidentally, this was close to where my great grandfather had operated his pottery at the turn of the 20th century.

There were 13 potters working in the studio and we normally fired the 100-cubic-foot reduction kiln 3 times a week. The Kuchs’ production line required accurate, precise sizes for thrown vessels. The beer steins had to be made to fit the pewter lids, so exact throwing was necessary. Once, the master came in and asked why I was throwing organ pipes instead of the specified sizes of the cups I was supposed to be making. My beautiful, one-of-a-kind masterpieces were casually tossed to the floor. It was excellent training. It kept me focused and gave me the skills to work with close tolerances when needed.

After my apprenticeship in Germany, I returned to Berea College to finish my final year. During that year, I also met Donna. The following year, I became the graduate apprentice at the school, produced pots to be sold at the college, and made plans for my future studio.

For many decades, I attended an annual potter’s gathering here in West Virginia, that brought in the world’s best potters for weekend workshops. I also received further training at New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University summer programs.

I am a full-time potter and average about 60 hours per week in production and pottery related tasks. Donna is my partner in the pottery and does a huge amount of the work that needs to be done: mixing glazes, loading kilns, and making slabware. Donna’s time in the studio varies depending on what needs to be done. Her training has been on the job and from many contacts with potter friends from around the world.

Our days always start with some YouTube yoga followed by a business meeting during breakfast. Donna and I cover old business, new business, and make a plan for the day. We work until lunch and then after a 15 minute rest, go back to the studio until 4, when Lucy, our lovable lunatic pup, insists we go for a walk around our fields and woods. We normally work a bit after dinner finishing and cleaning up, especially closer to the shows and during glazing cycles. We generally work in two day cycles: throwing or slab work the first day and trimming, assembling, and decorating the second day. We do not have any rigid divisions of labor. Every day is different and we both work either to make and finish the pots or to get food on the table.

Marketing

There were many quality craft shows and shops in the 1980s. For our first 15 years, we filled our van with pots and traveled the East

Coast hoping for good weather and appreciative customers. We averaged 12–15 shows a year, plus supplying half a dozen galleries with our pots. In the mid 1990s, while preparing inventory to go to a craft show, we realized that we didn’t have enough pots available for a decent showing because many pieces were on consignment at several different galleries. It was also increasingly difficult to fit the pots and our two sons into the van for the shows. At that point, we decided to try selling our work here at the studio rather than traveling to shows.

The studio shows and sales have evolved over the years. Experimenting with different show dates, we have settled on four shows a year. Postcard invitations, social media, articles in our very supportive local paper, and word of mouth are our best marketing tools. In 2001, we built a 40×40-foot garage/gallery building that allows the show to be set up early and accommodates our wide variety of pots. During non show times it houses woodworking tools, some of the wheels, and studio tools that don’t get to stay inside all the time.

We often have clay-related competitions at the studio shows. We were hearing from customers that they would play golf instead of coming to the pottery shows. So, we set up a canoe in the field and gave anyone $100 worth of pottery when they landed the golf ball in the canoe. We realized that the longer the customers stay, the more time they have to see the pots and the more they buy. We had a rule that while one person was hitting golf balls, their spouse or partner was to have possession of, and freedom to use, any and all credit cards.

The goal of these added events is for the customers to enjoy the shopping experience and the pots they go home with. Any exposure to wet clay and glazes helps the customer realize that there are skills involved in getting the clay to do what they have in mind. Competitions have included making a boat out of clay that floats and holds the most pennies or seeing who can throw the tallest pot on the wheel with a pound of clay. There are always wheels set up for demonstrations and to give visitors a chance to throw their own pots. We also have a raku body that has enough sand to permit immediate firing, allowing people to make a piece, fire it, and take their creation home the same day. Customers have told us they had to drag their kids to the shows, and then they have to drag them away. Many of these kids return years later and are now buying our pots for their own homes.

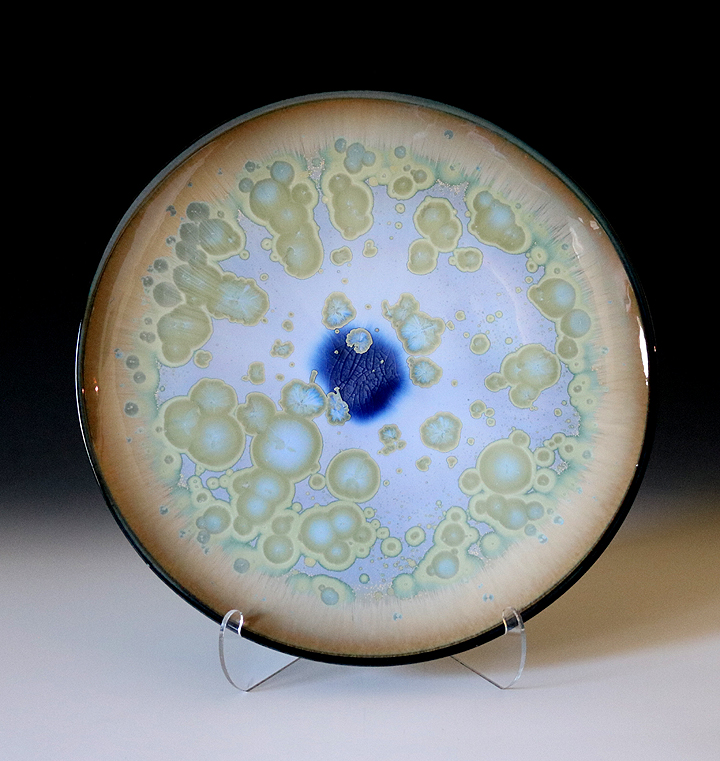

Because of the many repeat customers, we have to innovate constantly. The most common request at each event is “Show me what’s new!” We make a wide range of primarily functional pots and keep altering them and experimenting. We always have a show special introducing new items to our standard line. The need for changing surfaces and forms expanded our line from stoneware fired in reduction to stoneware and porcelain fired in salt and wood kilns, as well as developing crystalline-glazed ware that is fired in an electric kiln. All the kilns are fired to cone 9, so all the porcelain and stoneware clays can be fired in all of the kilns. Many of the 25 (or so) glazes are also used in all four kilns, giving us a broad palette and a range of surfaces.

We walk on a trail blazed by Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada. They lit the fire that developed the awareness of the human soul’s need to appreciate and value handmade pottery. This need for pottery has kept food on our table and provided our family a wonderful quality of life for 40 years.

Mind

We often spend long summer nights on the lake in our boat. The changing colors of trees and water and the patterns on rocky cliff faces feed my work, keeping the pots alive. International travel and teaching have opened many doors. Historical and contemporary pots from China, Korea, and Wales have given us a springboard for new forms, glazes, and decorations. Our studio and house have floor-to-ceiling shelving filled with both the work of other potters and pottery books. Teaching workshops and firing kilns abroad cultivates the desire to know more. All of this broadens our world, taking our conversation with clay to a new level.

Most Important Lesson

Phil Rogers once told me to strive to keep some decorations I was working on “spontaneous, but organized.” I found this suggestion helpful for the decoration I was working on and also good advice for life in general.

"Originally published in May 2020 issue of Ceramics Monthly, pages 20-23.

http://www.ceramicsmonthly.org

Copyright, The American Ceramic Society. Reprinted with permission."

Born of Clay, Fired by Passion

By: Cindy Martin

An article in West Virginia South

October /November 2016

Grounded by the stillness and beauty of their surroundings and set into motion by the energy of the earth, award winning master potter, Jeff Diehl, and his wife, Donna, are creative artists and visionaries. Moved by the majesty of the rugged landscape and the promise of an idyllic lifestyle, they purchased the two-room Lockbridge school house to make it their home and workplace.

“We were ready to buy another place in Summers County, but when we came for a final look, the realtor told us he’d just had a schoolhouse come on the market and asked if we’d like to see it,” Diehl explained. “So, when we got here, the front door was open and ‘God loves you and Zorro was here’ was written on the blackboard. I said, “This is it!”

Many of the neighbors who had attended the country school as children pitched in to restore and renovate the structure, which was re-christened Lockbridge Pottery. One of the old classrooms became Diehl’s studio.

Rooms were added. Repairs were made. And using stones from abandoned local buildings, the Diehls constructed the buildings that house the kilns outside where the stoneware and porcelain mugs and bowls, teapots and pitchers, dinnerware and trays, and custom sinks, fireplace surrounds and fountains would come to fiery life as finished pieces. They employ a variety of firing techniques, including salt, crystalline, reduction, and wood.

For over four decades, Diehl has spent countless hours transforming mounds of clay into purposeful pottery. “Most paper plates and plastic cups function very well,” he said. “I create pots that elevate the eating, drinking, and serving experience to a beautiful art form. My customers tell me the coffee tastes better in my mugs and the food being served is more beautiful on my trays and plates. I strive to create beauty in function and for the pots to function beautifully."

Diehl considers having his pots on the walls, in the kitchens and in the hands of his customers as being his greatest achievement. “I am honored to be a part of their everyday lives on such a personal level,” he said.

Following in the footsteps of his grandfather and great-grandfather who were both potters, Diehl followed the road less traveled while honing his skills and perfecting his art. After attending high school at Woodrow Wilson in Beckley, he studied at Berea College in Kentucky, where he served as Apprentice and Graduate Apprentice in the Ceramics Apprenticeship Program. Diehl also spent a year training in a studio in West Germany near his great-grandfather’s pottery.

Diehl draws his creativity from myriad sources and his work has been described as “unusual, unique, and amazing.” “I am inspired by historical pots, contemporary potters, natural landscapes, customer requests, dreams, or by emails from the bank indicating low balances,” he said smiling. “Iconic British potter, David Leach, came to Berea College while I was a student there and lit a fire that has had a profound influence on my work.”

Diehl has traveled extensively and visited potteries and museums in Germany, England, Wales, Korea, China, Singapore and Greece. Every culture has a clay tradition and potters are eager to share their skills and traditions. “As an American, I am not bound by tradition,” he said. “But I can use the world’s traditions as a springboard for my work.”

“What if?” is Diehl’s mantra. In his mind’s eye, questioning continually keeps the door open to endless possibilities. After reading “The Hidden Messages in Water” written by the Japanese scientist, Masuru Emoto, Diehl discovered playing musical arrangements while pieces were being fired in the crystal kiln produced very distinct patterns in the finished pieces.

Diehl’s work has appeared in many prestigious collections worldwide, including the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Korean Craft Museum, multiple Juried Exhibits and the Museum at the Cultural Center in Charleston. He has been the recipient of numerous accolades for his pottery and has taught workshops in Korea, China and many colleges and universities in America. Most recently, Diehl was awarded the 2016 West Virginia Governor’s Award for the Arts.

In addition to creating commissioned work, Diehl and his wife host several shows each year, where you can purchase his latest creations in pottery, as well as, traditional pieces from his extensive functional line.

Prior to leaving the nest, the Diehls’ sons, Erik and Andrew, were on hand to provide live entertainment for the shows at the studio. Erik now works for Steinway Pianos in New York and Andrew lives in Chicago, performing with his blues band, Andrew Diehl and the Nightmen. During the Labor Day Show in September, friend and fellow potter Nathaniel Krause assisted visitors in creating bowls to be sold to show support for the Empty Bowls campaign, an international initiative to raise awareness in the fight to end world hunger.

“We have had untold hours of help from family, friends, and neighbors to make this dream a reality,” Diehl explained. “We are constantly amazed and appreciative of the support we receive from friends far and near to keep these wheels turning.”

Pottery that Captivates the Hand, Heart, Eye

By LUCIA K. HYDE in Wonderful West Virginia Magazine

November 2003

Lockbridge Road in Summers County winds for several miles through rolling farmland, past houses and grassy meadows, before arriving at an old, two-room schoolhouse. The school sits well back from the road on tidy grounds. Clusters of flowers bloom around the broad front porch, and the school's canine mascot naps on the stone walkway. In the large field that stretches off to one side, you might expect to see a set of swings and a metal slide, but at this school, potter Jeff Diehl and his family have created their own sort of playground.

In his more than 20-year career as a full-time potter, Diehl has developed both a thriving studio and a lifestyle as beautiful, unique, and functional as his pottery. In 1980, Diehl and his wife, Donna, established Lockbridge Pottery by turning the abandoned country schoolhouse into a ceramic studio and home. Neighbors who had attended the school as children helped the Diehls remodel the beloved building. 'We have great neighbors,' says Diehl. 'They all went to school here. They have been invested in the care of the property and interested in our lives since we moved in.’

One of the old classrooms serves as Diehl's studio, where he spends 45 to 50 hours per week throwing clay. 'I always have fun in here,' claims the award-winning potter. Metal shelves filled with fresh, unfired pieces line the spacious room that also houses Diehl's potter's wheel and office. A collage of photographs, memorabilia, and artwork fills one wall and reflects his three loves: family, ceramics, and kayaking.

The Diehls added bedrooms and a kitchen, bathroom, firing room, wood shop, and newly finished gallery to the school. From the porcelain sink basin in the bathroom to the intricate kitchen counter tiles, evidence of Diehl's handiwork appears in every corner of the house. The Diehls have also used the building to raise and home school their two sons, Erik and Andrew. Both teenaged boys are accomplished potters, musicians, and kayakers. The whole family assists Diehl with glazing and firing his pottery. 'My family helps out tremendously,' says Diehl. 'They are a critical aspect of the operation.'

The family also helped Diehl construct one of the most unique features of the property is the traditional, German salt kiln. Using rocks salvaged from dilapidated local buildings, the Diehls constructed a round outbuilding to house the kiln. The practice of salt firing originated in Northern Germany, where potters used driftwood for wood-fueled firing. Sea salt from the driftwood left unique patterns on the finished pots. Potters in Southern Germany eventually refined the process into an established art form. During a single firing, Diehl uses up to 100 pounds of Morton table salt to achieve beautiful salt-pattern surfaces. He is among the few potters in the United States trained in the art of salt firing. Although Diehl fires a majority of his work in a gas reduction kiln, he feels a special fondness for his salt-fired pieces. 'I love the magic of salt firing. The finished product looks a lot like wet clay. It keeps the liveliness going.'

Diehl himself molds liveliness into his work. Wavy and slightly tilted bowls, tureens with elephant trunk ladles, and teapots with porcelain wheels are just a few examples of the way he blends elegance and superb craftsmanship with humor and, well, funkiness. Out of his wide repertoire of vessels, Diehl most enjoys throwing teapots. He explains that teapots demand the greatest range of skills to create an attractive and serviceable end product. He prides himself on the utility of his pottery. 'I want my pots to be appealing to your hand, heart and eye. I strive for beauty in function,' he says.

Diehl draws inspiration from a myriad of sources, including his family, customer ideas, animals, dreams, and other cultures. He occasionally decorates pieces with ancient Chinese Sung Dynasty peonies and lotus patterns. The idea for a wheeled teapot came from Han Dynasty rolling figurines. Diehl has looked to Anasazi and other Native American earthenware for patterns and such specialty items as rattle mugs. The exquisite glazes Diehl creates from raw materials make his finished pots true masterpieces. His ceramics appear in collections worldwide at such prestigious establishments as the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. He has won eight best-of-show awards at the Appalachian Arts and Crafts Show in Beckley, a merit award at the Mountain State Arts and Crafts Fair, a craft fellowship from the West Virginia Commission on the Arts, and a professional development grant from the West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

''I was born with clay in my blood,' states Diehl matter-of-factly. His great-grandfather worked as a potter in Germany and his grandfather had a studio in New Jersey. Diehl remembers playing with his grandfather's discarded pot shards as a child. His formal ceramic education began at Berea College in Kentucky. He studied in the college's ceramic apprenticeship program for four years and apprenticed for a year in Germany, near where his great-grandfather lived.

For the past six years, Diehl's national reputation, along with his large following of patrons, has enabled him to sell his work almost exclusively through home-studio shows and commissions. The Diehls host four studio shows per year that are a festive combination of games, music, pottery lessons, food, and, of course, an opportunity to purchase Diehl's work. Erik and Andrew jam jazz and blues tunes on piano and harmonica, and guests rove amid clay-throwing contests, golf-chipping games, and canoe rides. Diehl encourages his visitors to try making a pot themselves. He has developed special clay that allows for immediate glazing and firing in a fast-firing raku kiln. Guests can take home their own 'masterpieces' the same day.

'After 22 years, pottery is still exciting for me. It's never like a job,' muses Diehl, as he surveys a shelf stacked with beautiful vases, platters, bowls, and fountains. In those years, Diehl has built a successful studio, a loving family, and a legacy as one of West Virginia's best-known potters. And clearly, he is still having fun.